J. W. Anderson makes it new at Loewe Spring 2022

We’ve had the pandemic, and now we have to come out of it different. I think it’s a moment of experimentation. If you’re going to reset after this period, you need to allow a moment to birth a new aesthetic. Start again.

- J. W. Anderson in conversation with Vogue

Clothes can be armour as much as adornment. The best offence may be a defence – that best foot forward. The persistent pandemic has revealed that protection can be ugly, and humiliating – like a paper mask – or enchanting, like the crystal trend every witch b*tch and under 25 has now.

Anderson’s colour palette for Loewe’s Spring 2022 collection was girlish, but organic with it. Think more of the women of Waterhouse, rather than Mean Girls. Rose quartz, amethysts, jades, aquamarines, and carnelians shared a mood with a crystal shop. Despite the soft sensuality of these colours, their arrangement belied their softness. The models marched down the catwalk in constructions with surprising exit points for skin to shine through; geometric shapes sticking out of feminine soft curves, concealing them; and excessive flourishes of volume in the most unlikely places. The contrast between sweet sensuality and sharpness created the sense of a defensive femininity – but not a weaponised one. This wasn’t the sharply pointed business-bitchiness of Balenciaga or Balmain, with shoulder pads and stiletto boots that’d hurt if they caught you.

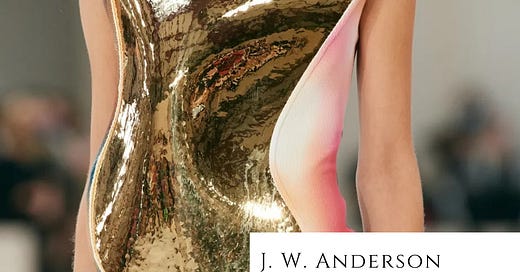

Loewe’s women are protected like Marianne Williamson is, with her shield of Virtue and sword of Truth. Golden and silver breastplates concealed classically structured dresses. And I’ve never seen anything like them on a catwalk before. The breastplates are reminiscent of shields and body armour – they’re giving Joan of Arc – they conceal the body in divine light.

In a collection that also featured head coverings more hijab than headscarf, the religious allusions inside these looks can’t be avoided. Models wore Berghain versions of the classic Joan of Arc chop. Anderson himself said Pontormo’s Deposition of the Cross was his inspiration for this collection, and his colour palette is the one Florentine artists imagined as heavenly from Giotto until the early 17th century. Any Bodhisattva would agree that appreciating beauty is as much of a spiritual practice to get close to the Godhead as any other, and these clothes are beautiful. The spirit’s elevated through admiring their contrasts.

Another defensive feature Anderson used was geometric shapes that emerged from inside the dresses outward, to obscure the feminine figure. The left hip became something pointed and sharp, whereas the right retained its fluidity. This defensive feature is as effective as the spikes on a hedgehog. It doesn’t stop the wearer looking elegant, willowy, or vulnerable – just like you know you can take a hedgehog, spikes or whatever.

Even more than the breastplates, the prisms protruding from the garments reveal the extent that this collection was made for art lovers. Anderson has always been a rare talent with his own agenda, but this collection was his purple patch – his great ability finally actualised its potential. I remain obsessed with the mediaeval elf trainers he sent down the catwalk for Spring 2018, and although that was brave, and smart, it wasn’t as refined as the looks he showed this season. Exhibiting in Paris, not so far from the Pompidou, was the perfect choice for this show so sympathetically related to the modernist avant-garde.

The prism-dresses were like wearable Constructivist sculptures, particularly the sculptural works of Antoine Pevsner and his Construction for an Airport most of all. Conceptual, elité art has never been a structurally sound vehicle for liberation, but it’s worth remembering the Constructivists were (originally) Bolsheviks; the dream being that when forms are liberated, the people’s imagination follows. Even if that’s a false hope, there’s still a gesture toward liberation in these looks – Anderson, like the modernist avant-garde, is creating new forms for a new world.

As the models progressed down the catwalk, there was a movement away from dreamy spirituality and modernist constructions to an entirely more ’60s tone. Many fashion journalists have already linked the #freethenipple Perspex panels to the opening outfit of Barbarella, but the revelation of skin, exposed in novel ways, wasn’t limited to tits. The knee cut-outs were particularly eye-catching. Either they were excessively adorned, with fabric blossoming around them like a wound, or simply unexpected – like dresses with a leg hole only on one side. There’s something subversive about these surprising entry/exit points that’s down to more than unanticipated skin’s erotics. The exposures are sexy, and delightful, because they’re slightly humiliating; they make the wearer silly – in a charming way – because they playfully expose, playfully make the wearer vulnerable. With Anderson’s vision behind this undressing, the mind turns to Lucio Fontana’s canvases (also a product of the ‘60s) with their unexpected slashes. Space where you don’t anticipate it is its own revelation.

Since Duchamp’s Fountain, much of the joy of contemporary art is in everyday objects appearing in unexpected contexts. Anderson took this conceptual principle and applied it to strappy sandals that surprised with heels made of roses, cracked eggs, soap and nail polish. This audacious elevation was joyous and happily daft. They read as a nod to found-object sculpture, but their cheekiness has something of Piero Manzoni’s Artist’s Shit about them. If shit can be a great conceptual artwork, a cracked egg can be a shoe. The confidence you need to send looks this weird down the catwalk is like the confidence required to insist you shit greatness.

Loewe Spring 2022 was brimming with moods and influences, but if there’s a coherent thread that binds these garments together, it’s vitalism. These looks affirm life in its diverse aspects. Sexuality is evident – the female form is celebrated. But so are other aspects of the human experience, often less valorised in high fashion. The exposed skin gives vulnerability; the prisms allude to aggression (think: “Though a quarrel in the streets is a thing to be hated, the energies displayed in it are fine” – Keats); the found-object shoes and knee holes in shiny dresses are silly, even funny; and intelligence is everywhere. You’ve got to be smart to know life is good enough to be affirmed like this, even in the age of coronavirus.